Jack Mullin

|

In July of 1945, a 31-year-old American soldier named Jack Mullin made one of the great career decisions of all time; he turned left instead of right. |

Jack Mullin recounts how his life changed after discovering the performance of the AEG Magnetophon, the first tape recorders used in Germany to record live performances and for broadcasting.

|

The story began in 1941 when John T. “Jack” Mullin joined the Army just before WWII. His background in electrical engineering landed him in the Signal Corps and in 1944 he went to England to help solve radio interference problems caused by the radar installations that blanketed Britain. Mullin became so intrigued by what he was doing that he would work till two or three in the morning, all the while listening to music on BBC radio broadcasts. The BBC always signed off the air at midnight. In search of continuing late-night entertainment, Mullin discovered that the German stations were on the air twenty-four hours a day, broadcasting symphony concerts all night that sounded too good to be pre-recorded. Shortly after the Allies liberated Paris, Mullin’s unit was reassigned there and given the task of evaluating captured German electronic equipment. In July of 1945, Mullin went to Germany to look into reports that the Germans had been experimenting with high-frequency energy as a means of jamming airplane engines in flight. While on the mission, Mullin met a British army officer who, after a discussion of music and recording, asked Mullin if he had heard the magnetic tape recorders used by Radio Frankfurt. The officer raved about the musical quality of these recorders and urged Mullin to go to the station to listen. Mullin had already heard and evaluated the poor-quality, DC-bias tape recorders used by the German Army, and thought, "Either this guy is on to something or he has a tin ear!" “On the way back to my unit, we came to the proverbial fork in the road," Mullin recalled. "I could turn right and drive straight back to Paris or turn left to Frankfurt. I chose to turn left. It was the greatest decision of my life." Mullin continued, "The radio station was actually in Bad Nauheim, a health resort forty-five miles north of Frankfurt. The station had been moved into a castle there to escape the bombing of Frankfurt, and it was then being operated by the Armed Forces Radio Service. In response to my request for a demonstration of their Magnetophon the Sergeant spoke in German to an assistant, who clicked his heels and ran off for a roll of tape. When he put the tape on the machine, I really flipped. I couldn't tell whether it was live or playback. There simply was no background noise." The advanced AC bias tape recorder was widely used in wartime German broadcasting. Mullin said, "The Magnetophon had been used at Radio Frankfurt and at other stations in occupied Germany by the time I stumbled onto it, but there was no official word that such a thing existed. The people who were using it to prepare radio programs apparently were unaware of its significance. For me, it was the answer to my question about where all that beautiful night-music had come from.”1 Later, Mullin would joke that, “The reason we didn't know about the Magnetophon was that the Germans never bothered to classify it as top-secret.” After sending the Signal Corps two Magnetophons that he had modified with the all-important AC-bias record circuit, along with extensive documentation, Mullin legally obtained for himself two unmodified Magnetophons under war souvenir regulations. During his last few months in the Army, he took the machines apart and sent them home to San Francisco in pieces because regulations specified that only a war souvenir that fit inside a mailbag could be sent. In total, Mullin shipped thirty-five packages, all of which arrived safely. Within three months, Mullin had reassembled the machines and fitted them with “American electronics” of his own design. After rebuilding the Magnetophons, Mullin showed them to audio professionals who were excited by the extremely high-quality sound and the ability to edit a first generation recording with no degradation. At the May 16, 1946 meeting of the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE, now IEEE) in San Francisco, Mullin gave the first public demonstration of professional-quality tape recording in America. Among the people in the audience who would later work for Ampex (the pioneering magnetic tape recording company) were audio engineers Harold Lindsay, Frank Lennert, Walter Selsted, and Charles Ginsberg (later of videotape recording fame). During the war, Ampex made tiny electric motors and generators for military use. The company was looking for a new post-war product. After hearing Mullin's demonstration, they made the decision to build America's first professional tape recorder; an audacious choice for a company with only six employees. |

AEG Magnetophon type K4 sp at the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting. Photo courtesy of the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting.

|

Until 1944, Bing Crosby had been doing Kraft Music Hall performances live on NBC. He hated the regimentation of live broadcasting and asked NBC permission to record and edit the shows well in advance of the broadcast. NBC flatly refused; they had a strict policy against pre-recorded programming. Popular legend has it that Bing went on a one- year hiatus at this point. Here are the facts from Museum of Broadcasting Hall of Fame member Jim Ramsburg, a fifty-year veteran of broadcast advertising and radio, and author of a forthcoming book chronicling network radio's Golden Age from 1932-1953: “One little known detail, Bing Crosby did not go on a hiatus over the [entire] 45-46 season. He didn't report to Kraft Music Hall in the fall [of '45]. Kraft sued him for breach of contract and replaced him from October through January with Frank Morgan. To settle the lawsuit, Crosby returned to Kraft Music Hall in February [1946] for 13 weeks. He lost .7% of his 44-45 ratings but still had the highest rated Thursday night program of 45-46. Nevertheless, 45-46 was the last time that Crosby ever scored over 20 in the ratings, (21.5). He dropped to 17.6 his first season on ABC, sank to 13.9 his second season and tanked at 12.6 in 48-49. “I define the broadcast season as the ten month period between September through June. Most all of the stars left the air for six to thirteen weeks every summer when listenership was way down, allowing them to pursue stage appearances, movies and other money-making activities or just go on vacation. “Going back to 1945, Kraft Music Hall was given to movie comedian Edward Everett

Horton in mid-May when Crosby went on his summer hiatus. When Crosby walked in

September of 1945, Horton kept the show until Frank Morgan was available in

October. Morgan took the show through January of 1946. Crosby returned from

February into May. He was replaced in early May with Eddie Duchin's Orchestra

and Horton again through June. So, in September of '46, Crosby returned to radio with a new show, Philco Radio Time, on the new ABC Radio Network (formerly the NBC Blue Network). Bing recorded the rehearsal and show on 16-inch transcription discs for editing into a final version for air. Unfortunately, recording and re-recording sound on discs created tremendous audio distortion, far inferior to the high quality of live broadcasts. Audiences reacted to the poor audio, ratings plummeted, and Philco threatened to cancel the show. |

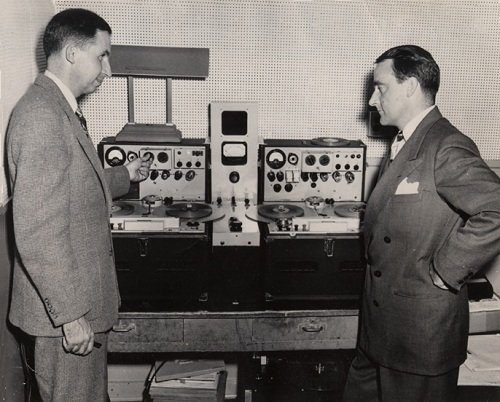

Jack Mullin and Murdo McKenzie. Photo courtesy of the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting.

|

In June of 1947, Murdo McKenzie, the technical producer of the Crosby show, drove to the Bay Area to hear a demonstration of the Magnetophon. McKenzie and the Crosby people were so impressed with the tape recording technology that they invited Mullin back to record the first show of the 1947-48 season that was to air on October 1st, 1947. At the end of the recording session, they asked Jack to stay and edit the tapes, including the outtakes, to see if he could make a finished program out of it. They were so impressed with the seamless edits and the lifelike audio quality that they hired Mullin, on-the-spot, for the entire season to master the show on tape for final transfer to on-air discs.2 With the two Magnetophons and fifty rolls of tape, Mullin was able to compile twenty-six shows, using his own techniques of splicing and editing. The foresight that led Jack Mullin to Bad Nauheim at the end of WWII was eclipsed by the hard work and brilliant decision making that followed, resulting not only in his successful editing of twenty-six consecutive Bing Crosby programs using two Magnetophon recorders and only fifty reels of German tape but also in the development of the Ampex 200 tape recorder, 3M audio tape, and the first video tape recorder. The story begins with an interview that Jack did for Billboard in 1972: “I remember well the first public demonstration I gave in San Francisco to the local chapter of the Institute of Radio Engineers on May 16, 1946. We had a large attendance and the enthusiasm was terrific. “Little did I know that night that among the audience were several men with whom I would later have a close and long association. Oddly enough, they were particularly interested in the sound of a small German loudspeaker I used as a monitor during part of my demonstration. They contacted us later, wanting to know if they could come to our studio to see it at closer range. We were, of course, happy to let them do so and they introduced themselves as Harold Lindsey and Myron Stolaroff, representing a small company of only six people in San Carlos on the San Francisco peninsula. They had been making aircraft motors during the war and were now looking for some new field of post-war promise. Since they were interested in high quality audio, they were considering the possibility of making speakers or even a disk recording lathe. Their company was headed by a gentleman named A. M. Poniatoff. Borrowing his initials and adding EX for excellence, they had named the company Ampex. Film Studio Demonstration “In October of 1946, Bill [Palmer] and I attended the annual convention of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE, now known as SMPTE). There were few references to magnetic recording, but one or two papers were scheduled for presentation on experimental work which was being carried on. In particular, I remember that Marvin Camras of Armour Research presented a demonstration of sound from a strip of 35mm film which he had coated with a form of iron oxide, using a paint brush. It sounded pretty good, but didn't seem to excite the sound departments of the major studios. “Col. [Richard] Ranger had come to the SMPE convention and he had accompanied us on these visits. He returned home with great enthusiasm, resolved to get into the business of making an American copy of the Magnetophon and its tape. We agreed to keep in touch, with the hope that W. A. Palmer & Co. could be his West Coast representative when he got into production. “The president of Ampex, Mr. Alexander Poniatoff, was also at the convention and we invited him to hear playbacks of some of the material we had recorded. Naturally, he was most enthusiastic and shortly thereafter the visible results of Ampex interest in developing a professional tape recorder began to be apparent. Because we had a verbal agreement with Colonel Ranger, I was not able to disclose to Ampex information I had learned in the course of development and use of the machines beyond what I knew from my activities in an official capacity while in the Signal Corps. Several months passed by while Col. Ranger and Ampex both developed machines and we continued to use ours in the studio in San Francisco. No further commitments on either side were made at the time and we returned to San Francisco. “By now, tape machines of reasonably good performance were beginning to appear on the non-professional market. Perhaps the best at the time was the Brush Soundmirror, which was considerably better than the quality of dictating machines, but well below professional requirements. Such machines had difficulty in finding their niche. They were closely watched by the 3M Company, who by now was making a paper base tape suitable for use on them. Crosby Tries Tape “Our tests of the 3M tape at this time indicated that it was not for use on the Magnetophons and, consequently, I had to carry on recording, editing, playing back and erasing the same original 50 rolls I had sent back from Germany. Col. Ranger meanwhile assured us that he would soon be making tape according to the German formula, and that his copy of the Magnetophon was coming along nicely. Ampex gave us similar reports about their recorder. “In July, we were informed that the first show for the 1947-48 Crosby season would be recorded in August at the ABC-NBC studios in Holly wood, and we were invited to be there, in the recording department, to take it on tape while they recorded on disk. “Concern was expressed for the fact that we had only the two original German machines and a limited supply of tape, but we assured McKenzie and Healey that we soon hoped to have backup machines and tape from Col. Ranger. “We contacted the Colonel and found he was confident he could be present at the recording session to give such assurance with two completed machines and, hopefully, some tape of his own fabrication. Ranger Machines Tried “We were able to set up our machines in a day or two in advance in the recording department at NBC, not without considerable concern on behalf of Les Cully, head of the recording department, who wondered about this encroachment in his “never-never-land.” We then met Col. Ranger at the Union Depot. He had come by train and had indeed brought two machines with him, but alas, no tape. He set up his machines the next day. “Thus we came to the most unforgettable moment in my life. The show was performed in the early evening. NBC’s recording department took it down on several disk lathes simultaneously, while Col. Ranger and I recorded it on tape on our respective four machines. “Then, that awesome moment of playback. Murdo asked first to hear the Ranger machines. My heart sank! The distortion on the peaks was excessive and the background noise was too high. Murdo indicated “cut” and then asked me to play one of the Magnetophons. We were in! “That night, Col. Ranger and I had a long talk. He was convinced he had carried the development of his machine to a point of acceptability and that in any event he must now sell these two machines as they stood. He had put a lot of money into them and was anxious to realize some return. It was obvious to me that they were not acceptable to the Crosby people and I tried to convince him of this. Fortunately for him, he was able to sell both machines in Hollywood within a few days, with the assurance that he would at some time later update them to provide better quality performance. He sold them to Harry Bryant at Radio Recorders. We still needed backup machines if we were to take on the Crosby show, and even more important, we were going to need tape. We were not confident that we would get either from Col. Ranger and so we terminated our relationship. |

Rangertone tape recorder at the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting. Photo courtesy of the Pavek Museum of Broadcasting.

|

Crosby Goes To Tape “We immediately contacted Ampex and I can remember my excited enthusiasm as I called long distance to Harold Lindsey and Alex Poniatoff to convince them of the great opportunity that seemed to lay at their doorstep. They had already accomplished a great deal, but there was yet a lot of work ahead of them before they would have a completed recorder. They had no intention of trying to make tape. “A conference was held and the decision was made to let us take on the radio show if we were quite certain that Ampex would produce a machine within reasonable time. We would then have backup protection and the operation might ultimately be expanded to the use of tape playback directly to the network. The plan meanwhile was to record on tape, edit the tape into a show and then transfer it to a disk playing the single generation disk on the air. My limited number of reels of tape could then be reused over and over until, of course, they would be consumed in splices. But we hoped for relief before this would happen.” A 1989 article for Sound Communications tells more of the story: “Until Ampex came out with their Model 200 audio tape recorder and 3M came out with 112 tape, Jack used the same 50 rolls of I.G. Farben tape that he had brought back from Germany on the Magnetophons. Each show used seven or eight rolls of tape, which were then very tightly edited and finally transferred to lacquers for broadcast. They couldn't risk playing back a tape that had numerous splices over the air, but they made sure the disk playback was identical to the tape playback. “At the end of each show, Jack did not simply bulk-erase the spliced tape reel and start over. He disassembled the reel first, then sorted out the pieces of tape by thickness [to maintain consistent frequency response between the splices]. “In the beginning, Jack used scissors and regular Scotch™ cellophane tape to make his edits (there was no special splicing tape available.) The sticky tape had a problem: the adhesive had a tendency to bleed out and stick to the next layer of tape. To get around this, Jack rubbed all of his splices with a little talcum powder, rewound the tape, and then played the tape back. If the tape had not been replayed for a few days, he would have to repeat the talcum powder process all over again.”5 |

Mullin in an ABC radio network controt room with the only two "portable" Ampex Model 200 tape machines ever buiit (in oak cases on the left). On the right, early portabie Model 300 (black case). The Model 200s replaced Mullin's two, well-worn modified AES Magnetophones that put Bing Crosby on tape in 1947. Photo courtesy of Peter Hammar.

|

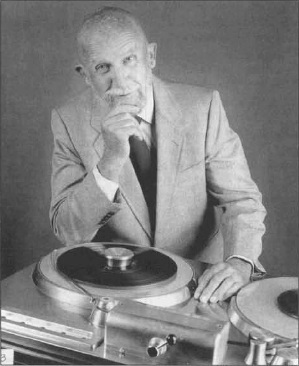

“What a relief it was to start afresh with brand new beautiful machines capable of running continuously for 35 minutes instead of only 22 and an inexhaustible supply of 3M tape.”6 Jack worked on the Crosby show until 1950. His growing interest in developing a magnetic video tape recorder prompted the creation of the Bing Crosby Enterprises Electronics Division, in which Crosby and Mullin invested. Jack was the division’s chief engineer. Bing Crosby Enterprises became the sole distributor worldwide for the Ampex audio tape recorders. ABC became the first customer, purchasing 12 machines for $5,200 each. They were followed by NBC, CBS, Mutual, Capitol Records, Columbia Records, RCA Victor, and Decca. In 1950, sales of wire and tape recorders totaled 110,000, in 1951, 100,000, in 1952, with wire recorders pretty much out of the picture, sales were 150,000 units. In 1953, 200,000, in 1954, 225,000, in 1955, 360,000 of which 60,000 were in the more than $600 class.”7 The next chapter in Jack Mullin’s life is best told by Pete Hammar, former curator of the Ampex Museum collection: “In 1949, Mullin told Crosby he could do for the star's budding television career what he had done for his radio career: put Bing on tape -- this time, on videotape. Based on Mullin's preliminary design, Crosby agreed to set up an electronics division of Bing Crosby Enterprises (sold to 3M in 1956, becoming their Mincom Division). By November 1950, Mullin and his small team had made enough progress to apply for a patent on his design for a ‘longitudinal-scan’ (no moving heads) magnetic television recorder. “Mullin faced the same obstacle to videotape recording as his competitors at RCA, the BBC, and Ampex: capturing the complex TV signal requires far more tape space than audio. Mullin’s first system used 11 fixed heads and ran its half-inch tape at 360 inches per second, twelve times faster than the highest audiotape speed, requiring 1800 feet of tape for each minute of video and audio. By 1952, Mullin and his team had made good progress reducing the problems of flickering and jittery images and were even experimenting with a color system. “Meanwhile, Ampex video R&D had been moving in another direction, using an idea first conceived by Chicago magnetic-recording pioneer Marvin Camras: a set of three (later four) video heads mounted on a rotating drum. The Ampex approach used two-inch-wide tape scanned transversely by the video-head drum, with a head-to-tape speed of 1500 inches per second. A standard-diameter 10-inch reel of the wide tape lasted for the one hour required by many network broadcasts. “Although Mullin’s fixed-head design -- along with similar longitudinal-scan approaches by the BBC and RCA -- couldn't compete with the Ampex method, Crosby's chief engineer goes down in history as having built the world's first working prototype of a videotape recorder, a project that motivated Ampex and others to begin their video R&D work. Jack Mullin is justifiably honored as one of the greatest innovators in the history of the technology so important to broadcasting in the last half of the 20th Century: magnetic tape recording.”8 |

Jack Mullin with an Ampex Model 200 Tape Machine. Photo courtesy of Peter Hammar.

|

Resources 1. Mullin, John T. "Creating the Craft of Tape Recording." High Fidelity Mag. April 1976: 62-7. 2. The Magnetophon tapes themselves were never played on the air. Only when 3M Scotch No.111 acetate recording tape arrived in the spring of 1948 with the Ampex Model 200A machine was magnetic recording finally used directly on the air. 3. Email from Jim Ramsburg to Steve Raymer 4/6/2009 4. John T. Mullin, “The Birth of the Recording Industry,” Billboard, November 18, 1972, 56-59, 77. 5. Mary C. Gruszka, “The John T. Mullin Story,” Sound Communications, February 1989, 42-46, 68. 6. John T. Mullin, “The Birth of the Recording Industry,” Billboard, November 18, 1972, 56-59, 77. 7. Mark Mooney, Jr., “The History of Magnetic Recording,” Hi-Fi Tape Recording, date unknown, 17.

8. Peter Hammar, “Jack Mullin, Videotape Recording Pioneer,” Pavek Museum of

Broadcasting Newsletter, March-April Foundational text and photos courtesy of the Museum of Broadcasting, Audio Engineering Society and Peter Hammar. |

Write about Jack Mullin!

Do you have content or pictures, to add, of Jack Mullin? Do you just want to say "Hello!"? Please feel free to Share it, here!

What other Visitors have said about Jack Mullin!

Click below to see contributions from other visitors to this page...

Memories of the Bing Crosby Enterprise Shop in Hollywood

My father, Eugene F. Brown worked for Bing Crosby Enterprises as a recording/mechanical engineer during the development of video on tape. My father was …

Return from Jack Mullin to Recording Engineers, Producers and Associated Recording Industry Professionals Return from Jack Mullin to History of Recording - Homepage |