Remastering Three Jazz Classics: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Art Pepper, and Sonny Rollins, by Bruce Bartlett

(This article co-authored by Jenny Bartlett.)

It’s a joy to hear old recordings of a favorite musician remastered on CD. Especially when the remastering is done so well that you can enjoy the music more than ever.

What’s more, a great remastering job clearly reveals the recording techniques used in the past.

There’s a lot to be learned about recording by studying how they did it so well, decades ago.

A stellar example is the four-CD Dave Brubeck reissue, Time Signatures—A Career Retrospective (Columbia/Legacy C4K 52945), produced by Russell Gloyd and Amy Herot.

It’s astounding how good some of those 30-year-old tapes sound!

The mix is just right. Cymbals are bright and crisp; acoustic bass sounds full; piano and sax are warm rather than thin. And there’s very little tape hiss.

The mastering job was ably handled by Mark Wilder, a recording engineer with Sony Music Studios (formerly Columbia Records). Since the 1970s, he’s worked at Vanguard Records, Polygram, and finally Sony.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet, circa the early 1960s

Bruce Bartlett: What was your philosophy in remastering the Brubeck tapes: to transfer them as is, or to clean them up?

Mark Wilder: In making the Brubeck compilation, we wanted the CDs to remain true to the original master tapes. Around 1984 to 1987, however, many CDs were remastered with a high-frequency rolloff (treble cut) to reduce tape hiss.

That was the philosophy of the time: to make remastered CDs hiss-free. Unfortunately, it was a destructive process.

Dave Brubeck complained about the sound of his early remastered CDs. Fortunately, we’ve learned a lot about remastering since then. I wanted to give him better treatment than that; I wanted to do it right. Our current philosophy is to adhere to what was on the originals. We don’t add equalization or reverb.

Sony’s new 20-bit A/D system helped to ensure a clean transfer from the original tapes to CD. It did the 20-to-16 bit transfer very well. Another current 20-bit Brubeck reissue is the Master Sound CD of Time Out. It’s so clear, you can hear bad edits onTake Five.

Bartlett: How does the sound of those early recordings compare with jazz recordings today?

Wilder: It’s amazing how well-recorded the group was back then. The sound is so three-dimensional, bigger than life.

Yet it’s amazing how little the engineers did to get that sound. They just put one mic a few feet from each instrument, and mixed live to 3-track—for left, center, and right. Then they edited the tape and mixed down to 2-track.

The old stuff sounds better than what we’re doing now. We’ve been going in the wrong direction sound-wise for many years. The layout of the stereo stage was more realistic then, too. Drums were on the left, piano on the right, sax and bass in the middle.

It’s easy to hear what each musician was playing because they were separated spatially. These days, you hear each instrument in stereo, on top of each other. The drums spread all the way between the speakers, and so does the piano.

In one Brubeck recording (Castilian Drums, not on this set), the stereo perspective changes radically within the recording. It starts with drums hard left and piano hard right. But when the drum solo starts, there’s an edit and suddenly you hear the drum set spread out in stereo.

At the end of the solo, you’re back to drums left and piano right. These effects are on Brubeck’s albums Countdown (Columbia CS 8575) and Time Further Out (Columbia CS 8490), .

Bartlett: How was the Quartet miked?

Wilder: Columbia was heavy into Neumann M49 and AKG C12 mics back then. Both are large tube-type condenser mics.

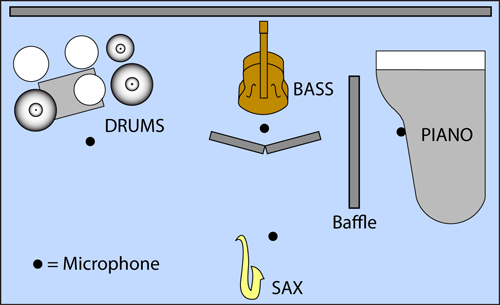

On the Brubeck groups, the engineers used one mic per instrument, and each mic was at a very respectful distance, about 1 1/2 to 3 feet away (Figure 1)...

You still hear all the air off the sax reed, and still hear all the tone. They got the placement quickly. Distant miking like this sounds great; I think we overdo close miking.

Bartlett: Some excellent photos of the studio layout and mic placement are in the liner notes of the CDs Time Out (Columbia Legacy CK 65122) and Jazz Impressions of Japan (Columbia Legacy CK 65726), and on the LP The Riddle (Columbia CL 1454).

Figure 1: Mic techniques used on The Dave Brubeck Quartet

Studio layout: Drum set on the left, bass a few feet away in the center, piano a few feet away on the right with the open lid on the long stick facing toward the other players. Sax faced the bass player a few feet away. The bass and piano were baffled. Baffles were placed behind the group as well.

Miking: Drum set—C12 about 5 feet up and 1.5 feet in front of the set, angled down toward the snare drum. Upright bass—U 47 about 1 foot from the bridge. Sax—M 49 up fairly high about 1 to 1.5 feet away. Piano—M 49 looking at the strings, about even with the curved edge of the piano, halfway between the soundboard and the lid. (This tends to emphasize frequencies around 500 Hz).

Bartlett: What was the typical recording and editing procedure in those days?

Wilder: Recording back then was almost a factory process. They recorded live to 3-track in three-hour sessions.

Then the tape went to the editor, then to the mixer, who mixed three tracks to two. Little or no compression was used.

We compared the master tapes with early pressings, and they were very similar. It’s amazing how little the mastering engineers did to the sound.

By the way, Columbia’s acetates were quiet as digital, even though theory says they aren’t supposed to be.

Studio engineers worked so fast back then. They might record Duke Ellington in the morning, Doris Day in the afternoon, and Brubeck the next day. There was only one hour between sessions, and each session had a totally different setup.

In spite of the speed of these sessions, you never hear a blown solo or a blown fader move. And there’s never a dramatic sound change at an edit point.

Bartlett: Who were the engineers on the Brubeck sessions?

Wilder: Fred Plaut and Frank Laico were two of Brubeck’s recording engineers. Plaut is a true balance engineer; he’s my idol. I don’t know how he could pull off what he did in three hours.

Besides Brubeck, another artist whom Plaut recorded was Michael Olatunji. He was an African drummer who made ethnic cultural records. When I listen to them, I’ve never heard drums sound so beautiful in my life—such color and harmonics. Why can’t I pick up a record today and hear that?

Plaut did a lot of Broadway recordings, and he worked so fast. Here’s an example. Friday night after a Broadway theater performance, the actors would come over and record all night. Then the artists would go back to the theater for the next performance. By Monday morning, the records would be edited, mixed, cut, and on the shelf ready to be trucked out.

Eight-track recording was introduced in the late ‘60s. Plaut backed up his 8-track recordings on a 3-track recorder. He always ran a 3-track as a safety.

I listened to some of his 8-track recordings done in the late ‘60s. The 8-track is a mess, but the live-mixed 3-track has perfect balance and blend.

One Reissue, Two Mastering Engineers

We’ve seen how one engineer remastered the work of Dave Brubeck. Let’s turn to another set of reissues with an interesting twist: they give you a choice of remastering engineer!

In an unprecedented move, Analogue Productions released two CD versions of Art Pepper’s 50’s classic, Art Pepper meets The Rhythm Section. One version was mastered by Doug Sax; the other by Bernie Grundman—two of the most respected engineers in the business.

Doug Sax masters all of Analogue Productions’ reissues, so why was Grundman chosen? It’s a story of who knows who.

The original recordings were done on the Contemporary Records label. Grundman was once an engineer at Contemporary; he knew Pepper’s album intimately as a fan and as an LP mastering engineer.

Since the album was one of his favorites, Grundman had always wanted to master the LP reissue.

Lester Koenig produced the original session, and his son, John Koenig, recommended Grundman to Chad Kassem, president of Analogue Productions.

Kassem decided to release two versions, one mastered by Sax, the other by Grundman, and both under John Koenig’s supervision. Kassem is letting audiophiles make up their own minds about which sounds better!

From the same company, another reissue with a choice of remastering engineers is Sonny Rollins’ 50’s jazz classic, Way Out West. Both Pepper’s and Rollins’ reissues are on 24 karat gold, limited-edition CDs, pressed in Japan by Superior.

Legendary engineer Roy DuNann recorded the original 1957 sessions at Contemporary’s studio in Los Angeles. DuNann used AKG C-12 and Neumann U 47 condenser microphones, which fed an Ampex 350 2-track tape recorder running at 15 ips.

In remastering, Grundman used his own custom electronics in the mastering console and in the Studer tape transport. He chose an Apogee A/D converter with a Harmonica Mundi redithering module. Grundman added reverberation to the dry master tapes using an EMT 250 plate and Ocean Way’s live chamber.

In his version, Sax used a Mastering Labs (TML) console, MCI tape machine with TML tube electroincs, and a custom TML A/D converter. Sax added reverb with a Lexicon 480L.

Thanks to the careful work of Wilder, Sax and Grundman, jazz lovers and audio technophiles alike can savor the quality of these pioneering recordings, whose musicality has yet to be surpassed.

Acknowledgements: The author gratefully acknowledges Mark Wilder, Joanne Sloane, Iola Brubeck and Dave Brubeck for their help with the Brubeck part of this article.

Discography

Sonny Rollins LP, Way Out West was originally Contemporary Stereo S7530. Sax’s remastered reissue is CAPJS 008, Grundman’s version is CAPJG 008.

Art Pepper meets the Rhythm Section was originally Contemporary Stereo S7532. Sax’s remastered reissue is CAPJS 010, Grundman’s version is CAPJS 010.

(This is a re-issue of an article originally written for the July, 1994 issue of Audio magazine.)

AES and SynAudCon member Bruce Bartlett is a recording engineer, microphone engineer and audio journalist. His latest books are Practical Recording Techniques (5th Ed.) and Recording Music On Location.

Write about Remastering Three Jazz Classics: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Art Pepper, and Sonny Rollins.

Do you have content or pictures, to add, on Remastering Three Jazz Classics: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Art Pepper, and Sonny Rollins? Please feel free to Share it, here!

Return from Remastering Three Jazz Classics: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Art Pepper, and Sonny Rollins to Recording Studio Sessions Return to History of Recording - Homepage |